This country witnesses only three or four movies in a year.

This is North Macedonia.

The last time a northern Macedonian film winning an nomination for Academy Awards (Oscars) was in 1994 for Before the Rain.

Honeyland has been nominated in the Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature and Academy Award for Best International Feature Film.

This is the first film to receive these two nominations at the same time.

- Honeyland -

The directors Tamara Kotevska and Ljubo Stefanov have originally intended to shoot a short documentary about nature close to River Bregalnica. However, they ran across Hatidze, thus beginning the shooting of Hatidze and her mother. Filming for two to three years, the two directors have carefully created this documentary out of the hundred-hour shot. This North Macedonian documentary will be screened at the Offline Screenings of the 10th Beijing International Film Festival.

- Half Taken, the Other Half Left -

Hatidze is a beekeeper, also the last beekeeper of the land, and she is of the Turkish origin. Many Turks moved to Macedonia during the Ottoman Empire, but many returned home from Macedonia (a part of the former Yugoslavia) when Turkey and the former Yugoslavia exchanged ethnic groups after World War II. But instead of returning home, Hatidze’s ancestors settled there forever.

According to customs of the local tribes, Hatidze must take care of her parents and cannot marry until they die, because she is the last daughter in the family. Day after day, she takes care of her mother in a dark cottage, harvesting honey in the wild.

The film opens with Hatidze traversing a cliff to reach a pot of gold, the only scene shot by a drone and a stabilizer. The scene is divided into two by the cliff. For the diagonal composition, the scenery under the cliff makes your hands sweaty. No phrase from Free Solo is too much for this scene, and this is Hatidze’s daily routine.

Despite the tremendous risks, she keeps her promise with the bees: “Half for me, half for them”.

She takes a half of the honey and leaves the other half for the bees to feed on, thus peaceful and harmonious co-existence. Following the conventional tradition, Hatidze takes care of her mother and leaves honey for bees.

It is not until a family moves in next door that the audience realizes how lonely she is and how desperate she is for a family. There are seven children in the family, and Hatidze becomes friends with them almost immediately. The children fill the emotional void for her. But as time passes by, the neighborhood has exerted a far greater impact on Hatidze's life than the director or the audience would have imagined. Almost instantly, Hatidze teaches her neighbors how to raise bees and harvest honey without any reservation, including her promise of "taking a half and leaving the other half for bees".

However, the family has seven children to support, while the patriarch is saddled with debts. Urged by the creditor to collect more honey for sales, the father soon breaks the agreement and drains the honey. Bees longing for honey flee to Hatidze's hive, killing her bees. As a result, no one has any honey, and the whole family is plagued by bee stings.

Only Hatidze leads a life as the conventional rules dictate, and she is like a contemporary person living in the 18th century.

- Life Scenes -

Without any deliberate conflicts, Honeyland presents life routines, yet which are very poetic.

Hatidze was born in 1964. When the shooting got started, she was 50. Yet, the hardships have made her far older than she was. She lives in a ramshackle house with no decent furniture, but the biggest problem is that there is no electricity. After discussion, the team decides to give up LED lighting and use light from the small window, candles and oil lamps to create the effect of a "Dutch painting in the 18th century".

They have also made effective use of the smoke in the house. Without a chimney, Hatidze’s home is heated by a stove. Thus, it is often filled with smoke inside, which photographers use to highlight the light coming in through the windows. The smoke, making photographers dizzy, is inhaled by Hatidze each day. However, under such smoggy circumstances lives Hatidze.

Hatidze speaks a Turkish dialect, which could be hardly understood by the crew. They were often shooting purely from a visual standpoint and did the editing in accordance. Only when they got translation of what they have shot could they encounter surprises. Hatidze asks her mother whether she could imagine the coming of spring. Her mother replies: Is there any spring? Too many winters have passed. Those poetic moments and debate about life and death often take place unexpectedly. Hatidze does not look forward to a different life.

She gets herself into trouble after her neighbor has messed up everything. She tells a sensible son of the family, "If I had a son like you, everything might be different." She asks her mother, “did you reject all who had proposed to me?” Desperately, she cannot help longing for another life, for a family she has never had the chance to start, for a family who is willing to take her side and support her.

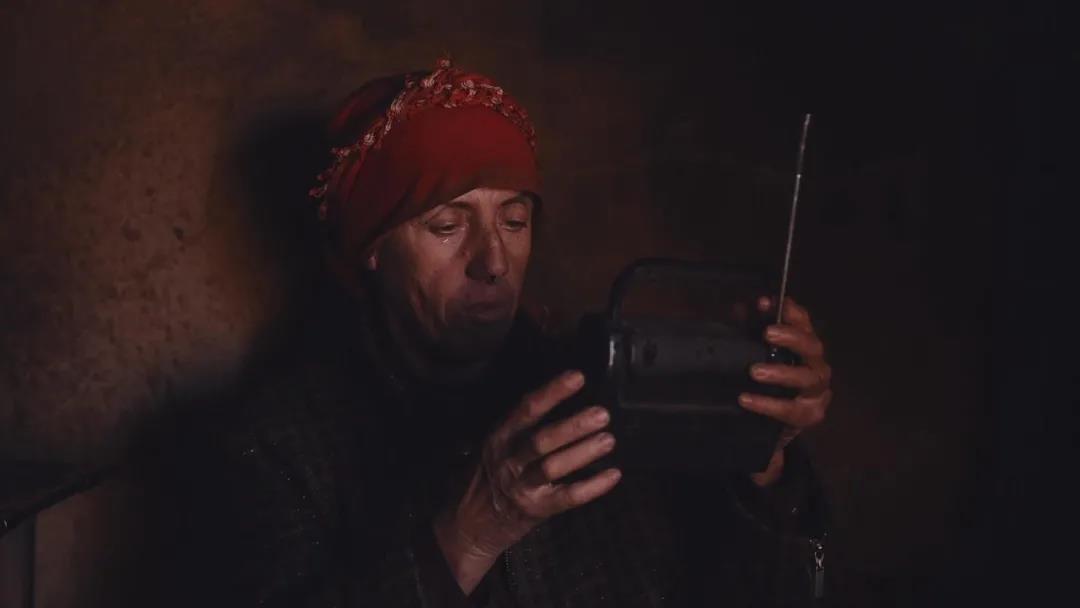

Eventually, everyone has left. Yet she is holding up a radio of poor reception, listening to a popular English song with tears in her eyes. The graphics are half dark. She has a face of an ancient tribe, but what she listens to is a modern song.