Market

Project Pitches Training Camp - Cheng Ma's Mentor Class: Cinematographers Should Focus on Helping Films Find Their Style, Not on Personal Aesthetics

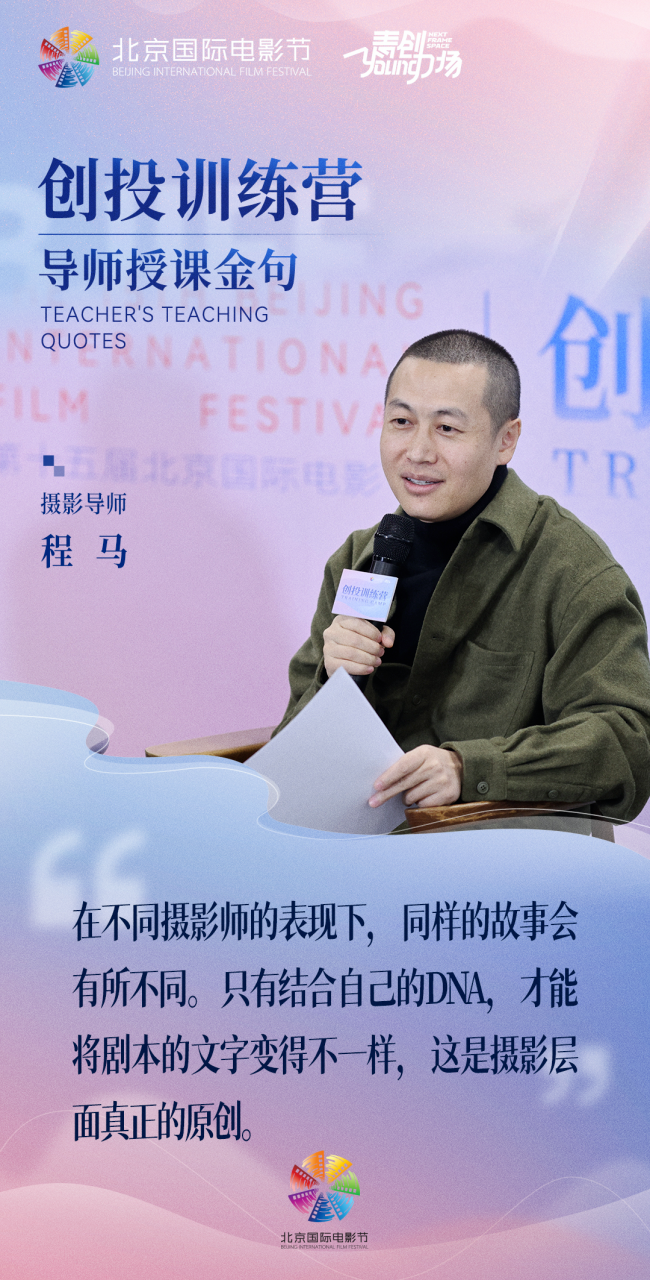

At the Project Pitches Training Camp during the 15th Beijing International Film Festival (BJIFF), cinematograpy mentor Cheng Ma delivered a class in which he shared his insights, drawing on his personal creative experience and industry observations. His humorous and incisive style, combined with his pragmatic viewpoints, resonated with the trainees and provided young filmmakers with comprehensive inspiration from both technical and conceptual perspectives.

Key Insights from Cinematography Mentor Cheng Ma

▍ Cinematography Creation: The Balance of Visual Transformation

Cheng Ma, who has worked on projects such as Duckweed, Lost, Found, My People, My Country, Fire on the Plain, Deep Sea and Only the River Flows, emphasized the creative power of cinematography in script. He believes that scripts should avoid overly detailed descriptions, especially those that predefine specific creative details for cinematography and acting, to allow ample space for secondary creation by the cinematographer. When it comes to visual transformation, he suggested that cinematographers should leverage their personal growth and life experiences. If these experiences are insufficient, they should explore other media outside of film rather than directly copying references that have already been transformed into cinematic images from previous films.

On-Site Sharing by Cinematography Mentor Cheng Ma

As a cinematographer responsible for a film's aesthetic style, visual form, and technical execution, Cheng Ma shared various issues concerning operational considerations. For instance, during location scouting, he stressed the importance of finding the right locations, even if they come with operational limitations. "Sometimes limitations can become part of the film's unique feature," he noted; however, when facing such limitations, a well-thought-out plan is essential. "A good plan must respect both creative and production principles, finding a balance between the two," he explained.

Regarding collaboration with actors, Cheng Ma believes that cinematographic design should serve the actors' performances to better capture the essence of a scene. As for communication with production designers, his advice is to avoid empty talk and instead patiently use specific visual aids such as location sketches, prop drawings, and material samples for set construction to facilitate detailed communications. He also recommended production designers seeking input from cinematographers and lighting technicians in the design and implementation of prop lighting.

▍ Practical Experience: Breaking Through Visual Styles

Cheng Ma has worked on three films set in the 1990s, each with a distinct visual style. Only the River Flows has a dark, absurdist tone; Fire on the Plain is characterized by its harsh and heavy atmosphere; and Duckweed features a warm and cheerful aesthetic. By deconstructing the unique visual temperaments of these different styles, Cheng Ma shared his experiences based on these three works.

On-Site Sharing by Cinematography Mentor Cheng Ma

Reflecting on the determination of visual style for Only the River Flows, Cheng Ma noted that the original novel's avant-garde nature required a balanced approach. If the film's style were too formalistic, it would appear glib and frivolous, lacking a sense of substance and depth. A realistic style, he argued, could anchor the story and blur the line between reality and surrealism for the audience. Conversely, if the story itself is highly realistic, the visual expression could be more imaginative to add interest to the film, he added.

For Fire on the Plain, which features extensive snow scenes, Cheng Ma emphasized the importance of thorough preparation in challenging the harsh natural environments during the filming process. However, he believes that factors such as weather and equipment are not the real obstacles in filmmaking. "The true challenge is whether your creative vision will be accepted by the audience," he said.

To solidify the tone of Duckweed, Cheng Ma drew inspiration from the tranquil and enduring works of Japanese photographer Ueda Yoshikazu. He used this romantic imagination to fill in his own gaps in experience regarding the affluent regions of Jiangnan in the 1990s. This displacement of inspiration allowed him to break free from the cliché of nostalgic sentimentality often found in period films.

▍ Contemporary Reflections: Aesthetics, AI, and Film Technology

Today, diverse filmmaking techniques elicit varied audience feedback. When asked about the public's acceptance of handheld shaky shot and breathing shot, Cheng Ma argued that the concept of public aesthetics is often misused. He noted that two films with similar box office results might attract entirely different audience demographics. Moreover, he observed that for high-grossing films, audiences tend to focus more on content and emotion rather than cinematographic form. In contrast, audiences of the auteur system films with more viewing experience are more sensitive to such issues. "Instead of worrying about how audiences perceive handheld shots, focus on the real expressive value they bring to your creation," he suggested.

On-Site Sharing by Cinematography Mentor Cheng Ma

Regarding AI technology, Cheng Ma advocated embracing new advancements, acknowledging that "the times won't say goodbye when they leave you behind." However, he noted that AI's current impact on cinematography is limited, mainly assisting in repetitive tasks during post-production color grading.

Regarding the so-called revival of celluloid film, Cheng Ma dismissed it as an illusion, citing market and industrial chain gaps that make it difficult for celluloid film to return to the mainstream.

▍ Advice for Newcomers: Collaboration, Communication, and Independent Thinking

When asked whether crew members from other departments should possess cinematography knowledge, Cheng Ma stated that while specific technical knowledge is not necessary, strong communication skills and a collaborative spirit are crucial. He emphasized that these qualities are more important than technical expertise.

Many young filmmakers struggle with balancing commercial appeal and artistic integrity. Cheng Ma shared his insights, "Commercial success relies on consensus, while art thrives on dissent. The greater the consensus in a film's values and emotions, the stronger its commercial potential. Authorial vision is about the filmmaker's independent thinking and original expression."

For newcomers who cannot afford high-end equipment, Cheng Ma offered practical advice to enhance visual quality: prioritize the subject, natural light, and post-production color grading. Cheng Ma believes that a low budget is not necessarily a disadvantage, "as smaller crews can be more agile."

Participants at the Event

Q&A

Q1: How to better manage film crew members with different backgrounds and achieve high production standards?

Cheng Ma: To achieve high production standards, either collaborate with professional and experienced talent or, if that's not possible, find people who share your creative vision and values and grow together. Instead of just pointing out problems, provide solutions and give your team the time, space, and opportunities to develop. Even seasoned professionals started as newcomers. Work sincerely with your team to deliver the project.

Interactive Q&A Session with Participants at the Event

Q2: What advice do you have for young directors and cinematographers working together?

Cheng Ma: Avoid bringing too many personal desires and egos into a project. When faced with suggestions from other creatives, think carefully, choose sincerely, reject boldly, and stay gentle yet firm. Avoid unnecessary distractions. Be sensitive in creation and insensitive in personal emotions.

Q3: Should a director of photography operate the camera himself?

Cheng Ma: It depends. In low-budget projects, saving costs is essential. But for multi-camera shoots, operating the camera can hinder efficiency, as you won't know the quality of footage from other cameras without checking and communicating shot by shot. Besides, I find that when I operate the camera, I can get too focused on the interaction between the camera and the actors. Sitting at the monitor gives a more comprehensive view and allows me to issue instructions promptly during shooting.

Group Photo of Participants and Mentor